5.27.2005

Representin'

Freestyling in El Alto, Bolivia. Photo by Noah Friedman-Rudovsky for The New York Times.

If you're a fan of hip-hop, especially intelligent and politically charged hip-hop, you probably know that rap has become a global language of protest.

Bolivia, in the midst of its new crisis (or, depending on your point of view, in the 473rd year of its age-old crisis) has given birth to a new form of rap. All thanks to one rapper, 22-year-old Abraham Bojórquez, who brought back North American urban culture from his stay in...Brazil. The movement is small, with just 20 rappers, but it's growing.

This Bolivian brand of rap might sound familiar to an American ear, but it is fueled by indigenous anger and culture. The lyrics are spoken in Aymara. The rhythms and instruments are also Aymara.

Juan Forero of the New York Times covers this nascent artform in a recent article and a killer audio slideshow -- highly recommended!

Aymara culture, old skool and new. Photo by Noah Friedman-Rudovsky for The New York Times.

5.26.2005

The Month of Living Dangerously

20,000 angry protesters can't be wrong... Or can they? Photo by AFP.

Ok, we're back from a little break...

I've blogged a whole bunch on Bolivia. Bolivia, that beautiful, but sad country, which for the past few weeks has been inching toward chaos. I'm not knowledgeable enough to explain the cause of Bolivia's troubles other than to say that it's about natural gas. Bolivia has lots of it. And a bunch of folks, mostly indigenous Aymara and Quechua, think it should be nationalized.

Over the past week, some 20,000 protesters (I've also read 40,000 -- it's difficult to verify the numbers) have flooded La Paz and have been marching, throwing stones, breaking windows and tossing sticks of dynamite at police. And throughout the country, they've also set up roadblocks, which have effectively brought the country to a halt.

Where's all this headed? It's anyone's guess. The protesters are in the city and don't appear eager to leave. The President, for his part, refuses to leave office. The military for the moment is not stepping in, as some might expect. And the police and have been reluctant to use excessive force, remembering all too keenly how the deaths of some 60 protesters in 2003 caused the downfall of the previous President. This weekend is a religious holiday, so the protesters are on hiatus. But they're vowing to be back on Monday.

Karl Penhaul has an interesting take on the conflict in his article on CNN.com, in which he describes the conflict as "a fight against the free-market economic policies and globalization...a battle between the haves and the have-nots, between the downtrodden and desperately poor Indian and mestizo majority against the political and economic elites." Pretty strong language, but probably right on the money.

Eduardo at Barrio Flores, himself a Bolivian-American, asks, "Who is repressing who? ...these scenes of war demonstrates that this is not a one-sided affair, where marchers are always the victim...Let us hope that no firearms are thrown into the equation."

Yes, indeed.

5.18.2005

Jim of the Jungle

Jim Thornton, being painted with herbal dyes in preparation for a futile anteater hunt. Photo by Olivier Laude.

Jim Thornton is one of the few people about whom I get to say, "I knew him when..." I met Jim many years ago taking his magazine writing class at the Loft Literary Center in Minneapolis. I'm pretty sure I never finished the main class assignment, but I do fondly remember finishing plenty of beers after class at Johnny's, where Jim held court.

Nowadays, instead of teaching, Jim does. You might see his features in such publications as Men's Journal, Details, Sports Illustrated, Self, and many more. For National Geographic Adventure, Jim has written Oddventure, a column that follows a simple formula -- send Jim into situations in which he's likely to be maimed and then watch the hilarity that ensues.

In one column ("Jungle Apprentice," Oct. 2004), Jim documented the weeks he and photographer Olivier Laude spent among the Huaorani tribe, deep in the Ecuadorean rainforest -- a group that until 40 years ago had never witnessed the blinding white of pale North American flesh.

Read an excerpt from "Jungle Apprentice"

View a gallery of photos from the trip.

Existential crisis, revisited

There but for the grace of God: A house in a shantytown on the outskirts of Lima. Photo by Rebecca "Rebel" Verner.

Many moons ago, I visited Perú for the first time as an adult. I was a second-year art student and somehow piggybacked an independent study on top of my vacation. So, I dutifully brought my sketchbook along, hoping to fill the pages with brilliant observations and fodder for future paintings.

To be sure, everything I saw was new and visually stimulating. But I returned to Minnesota with only a handful of half-hearted sketches. I had tried doing some pieces on the shantytowns, or "pueblos jovenes" outside Lima, which, for all the misery they embody, do have a certain visual beauty. But in the face of such mean poverty and a civil war that was in full swing at the time, the act of drawing or even thinking about art felt, in a word, selfish.

By contrast, I've had no problems taking pictures on any subsequent trips. With photography, I'm able to tell myself and believe that it's worthwhile, because I'm documenting the experience and the place. If it happens to be artful, all the better. And with this blog, the photographs become even more important. They serve as catalysts for discussion and reflection about how and why the world is how it is.

The photo above, by the way, was taken by Rebecca Verner, whose nickname is Rebel. She has two sites that are very interesting. Rebel's Peruvian Adventure documents her experiences volunteering at an orphanage in one of Lima's poor neighborhoods. It's a good, uplifting read and there seems to be a new development every day. Her Flickr site contains photos that help to illustrate many of her blog entries.

E-commerce for real people

On several occasions, I've gone online to order flowers, cakes, liquor and other goodies to be sent to my relatives in Lima. Tried a couple of services, but the one I like best is called Iquiero.com. This is a service that began in Perú but has since expanded to serve Colombia and Bolivia. The premise is simple: there are millions of latinos in the U.S. who besides sending money back to their relatives, want to be able to send the occasional birthday or Christmas gift without a two-month delay or the risk of theft-by-mail-employee. This site lets you send gifts quite easily, and by our economic standards, quite inexpensively.

Best of all, since labor is so inexpensive in the destination country, you get hand-writen confirmation emails and the goodies are hand-delivered by living, breathing human beings who don't ring the doorbell, leave a post-it and run back to their brown trucks. Nice touch: they'll even capture a thank-you message from the recpients, which is promptly emailed to the sender.

What I find fascinating is that besides ordering every kind of consumer product imaginable, you can use Iquiero to stock someone's pantry. They offer baskets of staple ingredients at several price points. The biggest basket costs $52 and includes the items below. (I didn't include the package sizes, but some of the items are indeed family size.)

I wonder what these items would cost in the States, if ordered through an online grocery company? For someone living and working in the U.S., $52 would seem like a pittance, yet it could set up a loved one with enough groceries for a week (remember, big families).

If one could find the name and address of a family that is struggling to feed their kids (and believe me there are lots of them) , it would be a lot of fun to surprise them with a gift like this. It would be the "random acts of kindness" thing, done up e-commerce style. Anyone game? I'm sure I could dig up some names from my friends...

The "Complete" Grocery Basket, from Iquiero.com

- 3 cans of tuna

- 1 pack of soda crackers

- 3 bags of rice

- 2 bags of sugar

- 2 bottles of cooking oil

- 3 bags of beans

- 2 packs of noodles

- 1 bag of oatmeal

- 1 jar of marmelade

- 1 bag of table salt

- 1 jar of mustard

- 1 bottle of ketchup

- 1 bag of flour

- 6 cans of evaporated milk

- 1 large can of coffee

- 1 can of cocoa

- 1 can of peaches

- 1 can of fruit salad

- 1 can of spaghetti sauce

- 1 can of gelatin

- 1 envelope of chicken bullion

- 1 box of chocolate pudding

- 1 envelope of pudding

- 1 bottle of vinegar

5.17.2005

Alto riesgo en Barrios Altos

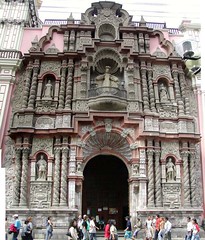

Virgen de Carmen church in Barrios Altos, Lima, Perú. Photo by Patrick Barry Barr.

A couple of posts ago, I mentioned the church in Lima where my family has attended for many years and where the sisters in the adjacent cloister make an ancient dessert out of key limes and dulce de leche. Well, not having any good photos of the church, I prevailed on a friend in Lima, Patrick Barry Barr (also the star of a recent post) to snap a few shots for me. Below is the tale of his near-mugging, as he so kindly ventured into this notorious neighborhood...

"Last Friday morning, the 13th, we took a taxi to the street. Somebody in the adjoining school told us that if we waited at the gate it would be opened around noon. I started taking pictures of the building from across the street, with her close by my side.

A woman, passing by, obviously having read our minds, stopped to tell us that Senora del Carmen was about three blocks down the road. So we took off, walking.

When we arrived, I immediately started shooting, with her again close by my side. I shot this and I shot that, making sure I got just about everything Don may need for his journal."

Interior, Virgen de Carmen church. Photo by Patrick Barry Barr.

"Of course, everybody in sight was curious. I barely noticed a bunch of guys standing in the street just outside the church compound. We were standing just inside the church, but outside the entry to the church itself, when a young woman, maybe 19, approached us with her baby in her arms, and, quite softly, told us the area was dangerous and that there were some robbers outside. I thanked her, without looking at the guys, so it would appear as just an ordinary conversation.

At the urging of my friend, we left the church compound, and waited just outside for a cab, which we got within seven minutes.

Then, in the comfort of the cab, my friend started talking about how terrified she had been. The taxi driver concurred that this wasn't the kind of neighourhood that we should be in, albeit as close as a quarter mile to the Congress.

My friend told me that she saw the guys coming together, that she looked them in the eyes, that one of them had razor cuts on his face, that she thought they were reluctant to rob us on church premises and that she heard one tell the group to move further down the road.

When I told my landlady about the experience, she recounted that there is a gate that leads into a residential compound and that when the robbers snatch some prize and run through those gates you can kiss your property goodbye.

In many areas of Lima, it appears to be a No Man's Land and the police think better of going there.

One midnight, about 4 years ago, as I sat in a tiny bus (a Combi in Lima) on Avenida Venezuela, the driver waiting to get it filled before leaving, I saw a guy outside casually shoving his hand into a man's pockets, as if they were his own pockets. And everybody behaved as if it were quite normal.

There are some parts of Lima, like some parts of just about any city, where you are better off avoiding altogether."

5.16.2005

Nobilidad

Visca collecting rainwater, Moca, Republica Dominicana. Photo by Jezmin.

Jezmin recently returned to the Dominican Republic for her grandfather's funeral and took this picture. Her narrative follows...

"I shot this picture in my grandfather's house located in Moca, Dominican Republic.

This area is relatively poor and potable water is very scarce. My grandpa built this water tank many years ago to hold rain water.

Neighbours (especially women) regularly come by to carry water back to their homes, using big 'cans' as you see in the picture. They wrap a piece of clothing in their heads, arranged like a big donut, to support the can in their heads.

Since I was a child it was fascinating for me to see these women carrying the water so easily (and they looked so tall!). They also carried more things with them: sometimes a baby in one arm, and holding a child with the other.

And of course, they had perfect posture. The way they walked was very noble.

Visca is a Spanish petname for a person that is crossed-eyed. I've known Visca since I was a child, but I don't know her real name. I hadn't seen her for several years when I took this picture, and while she must be old, she hasn't aged a bit."

5.13.2005

Rostros de alegría

Girls goofing around in Soacha, Colombia.

A boy in school in Otavalo, Ecuador.

Sisters playing while their dad works, Soacha, Colombia. All photos by Anne-Karine.

Anne-Karine is a traveler from Montréal who has a gift for capturing the innocent joy of the children she meets. Her photos of Colombia and Ecuador are few, but delightful.

5.12.2005

Gift from the Sisters

Photo by Don Ball. Lots more family photos at my Flickr site.

In the foreground is a wedding gift to my cousin Rosa from the Sisters at Virgen del Carmen, an ancient cloister in the Barrios Altos neighborhood of Lima. My family has attended the church there for years and my abuelita would chat on the phone with the "madrecita" nearly every day.

The gift itself is a cultural treasure: it's a colonial era sweet that has nearly been lost to history. Can you make out the foil-wrapped balls inside the basket? They are key limes, which have been halved, hollowed out and candied, then filled with manjar blanco (a thick caramel also known as dulce de leche) and then rolled in powdered sugar. It takes hours to make these things and to my knowledge the sisters are the only ones left in Lima who make them.

5.11.2005

Parácas, Perú

Natural arch along the central desert coast. Photo by Jackson Lee.

5.10.2005

Illimani at sunset

The imposing massif Illimani, as seen from La Paz, Bolivia. Photo by Greg McGee of Ultra Ridiculous Mountain Guides.

5.09.2005

La cocina de mi abuelita

Everyday life in my grandmother's kitchen. No single room in Peru holds more good memories for me. At left is abuelita herself, who passed away recently at 95 years old, give or take a year (nobody knows for sure!). My tía Chabuca (center) cared for abuelita, her mother-in-law, until the very end, even though she had been widowed for some 15 years. My cousin Martín (right) is an engineer in his early 30s and continues to live at home and contribute to the family's well-being. All this is customary in Perú, where family comes first.

5.05.2005

Helping kids climb out of poverty

Colonia Ecologica's new building, in progress.

Colonia Ecologica, in Cochabamba, Bolivia, is a home for 17 orphans or former street children that "offers prevention, protection and promotion: preventing more children turning to street life, protection and safety in a happy family and promotion of responsibility and moral values."

Some of the girls of Colonia Ecologica.

Claire Hamnett and Gertjan Janszen, the British and Dutch wife-and-husband team who run Charity Bolivia, are trying to raise money for Colonia Ecologica by promoting an annual climb to Cerro Tunari, the mountain peak just outside of Cochabamba (below) during the students' holiday break in June. Approximately 13 of the children, ages 10-17 will be participating in the four-day hike.

Cerro Tunari, as seen from Cochabamba, Bolivia. It's 2 1/2 days to the peak and 1 1/2 days back.

Ah, the wonders of the Internet! You can donate even a small amount on Claire and Gertjan's site via Paypal. (You'd be amazed how far $10 will go in Bolivia!)

5.04.2005

Ghost train

5.03.2005

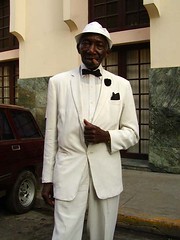

Despots 'R Us

May Day parade in La Paz, Bolivia. AP photo. Thanks to Eduardo Avila.

Many years ago, I concocted a beautiful Fidel Castro Halloween costume, complete with fatigues, beard, 60s-era horn-rimmed glasses and cigar. When I arrived at the party in Northeast Minneapolis, I was greeted by shouts of "Hey, Saddam!"

Groan.

When it comes to third-world leaders, there's a strange math that many Americans do in their heads and it goes something like this:

However, the scene above tells me that we're not the only ones who would put revolutionary leaders, tyrants and political cranks in the same boat. I suppose that's how it works when you're staring down the business end of globalization. Anyone who gives the bird to the world powers (and gets away with it) is indeed a hero.

Niño de Otavalo, Ecuador

5.02.2005

Argentine Idol

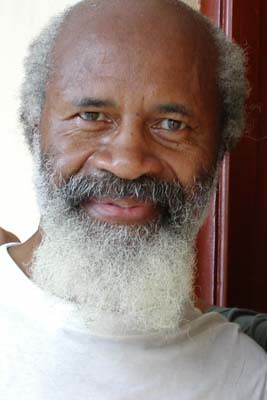

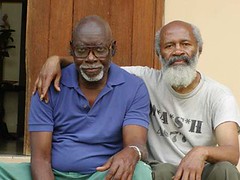

Meet Patrick Barry Barr

Patrick is truly a man of the world. He was born in Jamaica, educated in Wisconsin and then spent the bulk of his working years at the United Nations, UNICEF and AT&T Public Relations.

Today, retired and living in Lima, Patrick traipses the streets of the city with his digital camera in tow. He also takes occasional trips to other interesting places, including NYC, Europe and his favorite country, Cuba. He posts his photographic observations on his photoblog.

To save you from losing the rest of your work day on his site, let me show you some of my favorites from his blog:

Lima, Perú

St. Petersburg, Russia

Kingston, Jamaica

La Habana Vieja, Cuba

Perú Negro

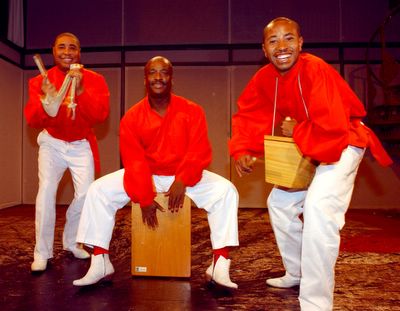

Perú Negro's percussion section, demonstrating uniquely Peruvian instruments. Photo by Gilmar Lopez, courtesy www.perunegro.org

It's a sad history that has parallels in North America. During colonial times, African slaves in Perú were not permitted to play music using drums and other percussive instruments. So, they invented entirely new instruments using available materials, including (above, from left to right) the Quijada, the Cajón and the Cajita.

Dan Rosenberg at Afropop.org tells the history of these instruments quite wonderfully:

"In much of Africa and the Americas, scrapers and shakers are frequently made by cutting ridges into gourds, or by attaching shells to them. Black Peruvians, of course, have a different tradition. They use the quijada de burro, literally the jawbone of a donkey. They take an old jawbone from a dead donkey, let it dry out, and loosen the teeth. Then, when it is struck with the palm, it produces a wonderful shhhhh-tshhhhhh sound. Running a stick along the teeth allows it to double as a scraper. While Peru isn't the only place that uses the quijada, it is the place most strongly associated with this unusual scraper and shaker.

Flamenco fans may have seen legendary guitarist Paco de Lucia with a cajon player in his ensemble. When Paco de Lucia visited Peru nearly 20 years ago, the Spanish ambassador threw a party. Among those present was Caitro Soto, one of Peru's top percussionists. Soto gave de Lucia a cajon as a present. He also gave the guitarist basic tips on the instrument, which has now become a standard part de Lucia's flamenco ensemble. Ironically, today, many people think that the instrument is Spanish. It is 100% Peruvian.

Another one of Peru's famous musical instrument boxes is the cajita. Imagine a trapezoidal shaped box about the size of a child's jack-in-a-box. One hand opens and closes the lid while the other hits the box with a wooden stick. The cajita also had Catholic origins. It was adapted from the wooden boxes that the priests used every Sunday in church to gather the weekly collection. The result wasn't exactly what those priests had in mind."

In its performance, Afro-Peruvian music is visually stunning. The group Perú Negro offers a video sample (requires Real player) on their site. I also highly recommend David Byrne's compilation "Afro-Peruvian Classics: The Soul of Black Peru" as an easy and infectious introduction to this incredible music.